Europe is a region well known for its linguistic diversity and high degree of multilingualism among its citizens. There are 23 officially recognised languages and more than 60 indigenous regional languages. Then on top of this you have many non-indigenous languages that are spoken by migrant communities across Europe, as stated by the European Commission in its comprehensive report on “Europeans and their Languages” from 2012.

Surely, with so many languages in play, how do you decide when and where translation is feasible, and when it is not?

Below I have compiled a few insights into how Europeans use and perceive languages, which are taken from the abovementioned report, commissioned by the European Commission and carried out by TNS Opinion & Social Network in the 27 Member States of the European Union.

It is a misconception that almost all Europeans are multilingual

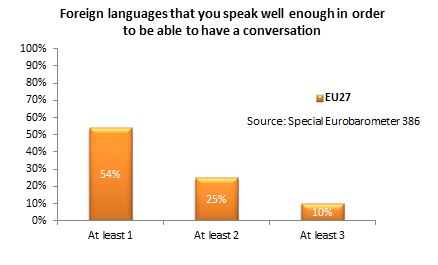

According to the report, 54% of Europeans are able to hold a conversation in at least one other language than their mother tongue, one in four speak two languages in addition to their mother tongue, and one in ten are conversant in three or more foreign languages.

While that is a lot compared to the global average, almost half of the region’s 740 million large population are monoglots (people who speak only one language). Moreover, when respondents were asked if they knew any foreign language well enough to communicate online, that number dropped to 39%. In other words, less than two-fifths of Europeans speak a foreign language to a level that enables them to communicate and engage online. For English specifically, the by far dominating foreign language in the EU, that number is 26%.

When you add to this that previous research has found that a whopping 9 in 10 Europeans prefer surfing the web in their native language, the amount of missed opportunity by having your website in, say, English only becomes very apparent.

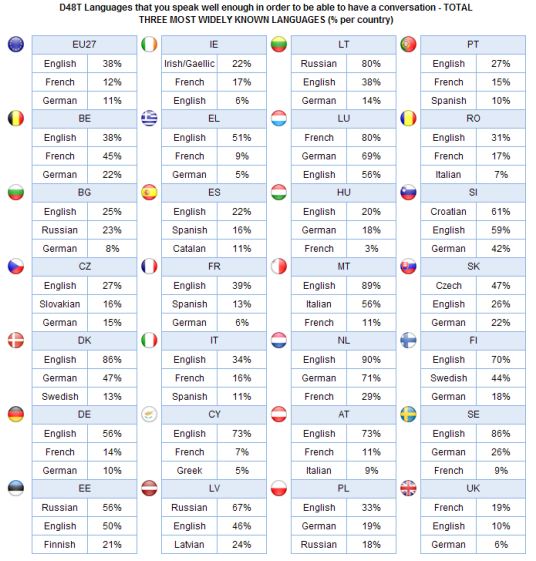

Which are the 3 most common foreign languages in each EU member state?

In 19 out of 25 Member States (excluding the UK and Ireland), English is the most widely spoken foreign language. Not only is English the most spoken foreign language, it is also perceived the by distance most useful foreign language, with 67% of Europeans naming English as one of the two most useful languages for themselves. This indeed puts it well ahead of German (17%), French (16%), Spanish (14%), and Chinese (6%).

French and German are the two most commonly used foreign languages after English; however, the report interestingly finds that, when correlating these findings with those of the equivalent 2005 survey, the perceived importance of knowing French and German have decreased rather notably. Put differently, these languages are not considered as useful as they used to be.

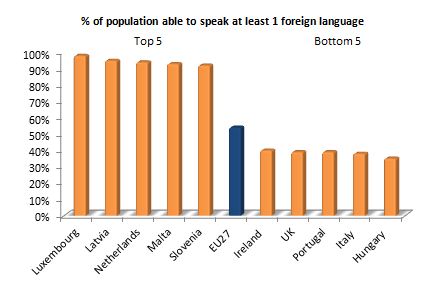

Degree of multilingualism greatly varies between EU countries

As can be seen above, there is also widespread national variation on the degree of multilingualism between European countries. To better demonstrate these outspoken differences, below I have compared the top 5 multilingual countries against the bottom 5:

This is extremely valuable information when considering whether translating a website is economically feasible. For example, it is plausible that it will not make that big a difference on your performance to keep your website in English if you are targeting Dutch consumers, however it surely will if you are aiming to make inroads in Hungary, Italy or Portugal – just to name a few.

In favour of multilingualism, but not at the expense of native languages

There is great openness amongst Europeans towards foreign languages; arguably an understatement given that more than 8 in 10 express that knowing languages other than their mother tongue is very useful and that everyone in the EU should be able to speak at least one foreign language.

Moreover, a majority of Europeans are in favour of being able to speak a “common language” across all EU Member States, however, 81% state that all languages should continue to be treated equally. That is indeed a very important catch, and it actually represents an increasingly favoured view towards treating all languages equally, compared to the 2005 survey. The report notes:

(…) although most Europeans support the notion that everyone in the EU should be able to speak a common language, this view does not extend to believing that any one language should have priority over others.

Multilingualism is NOT on the rise

There can be no doubt as to how enormous an impact multilingual proficiency within the EU will have on reaching the proclaimed objective of creating a truly integrated Europe going forward. Its impact on workforce mobility, competitiveness and finally overall economic performance of the Union in a global marketplace certainly should not be underestimated either.

While the internet is often described (and rightfully so) as this unifying force that brings us all closer together – be that geographically, culturally and linguistically -“there are no signs that multilingualism is on the increase within the EU.”

In fact, findings from the report show that there has been a small decrease in the proportion of Europeans who say they are able to speak a language in addition to their mother tongue, compared to the 2005 survey. This decline is largely driven by notable decreases in Russian and German proficiency in Central and Eastern countries such as Slovakia, The Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Poland and Hungary.

Having said that, the report does find that foreign languages are increasingly being used “regularly” on the internet, up 10 percentage points since 2005 and thus marking one of the most notable changes recorded during the period.

Closing thoughts

As each Member State is responsible for its own educational and language policies, a truly integrated, “common-language-speaking” Europe seems light-years away.

Also, bear in mind that being able to speak a language does not imply that people use it frequently, prefer it over their mother tongue, or actively go to seek out products and services on the web in that language. Hence, the most important thing to be aware of when jotting down your European expansion roadmap is the notion that there is no such thing as a golden rule, single-language or uniform cultural identity within the region.

However, since translating your website into the vast amount of languages that are in use within the region will often be an economical no-go, what you can do is create clusters of countries that share similar linguistic and cultural characteristics, e.g. English website for Holland and the Scandinavian countries, Russian for the Baltics and so forth. Then for countries with a low degree of multilingual proficiency, you will have to evaluate whether the economic potential matches the costs of translating your site. Targeting countries like Portugal, Hungary, Italy and Poland with a foreign language will simply be a waste of time, money and effort.

While such an approach often will not put you on even ground with your local competitors from a language point of view, you might be able to benefit from the economies of scale that come along with having an international presence. However, going back to the opening question of where translation makes sense, it should go without saying that the ideal solution will always be to target any given country in its mother tongue. And in many cases, it is absolutely essential to compete and ultimately be successful.

12 responses

Great article, Immanuel and some good solid data and insights.

I wanted to add a couple of elements on the subject of translation. When you consider the 81% that think languages should be treated equal, I think this is a form of National pride. From the user perspective there are of course various ways of searching for information and if you simply need that 1 element of crucial information, you will be willing to accept it in any language. As such, I do many information searches in English although my work environment is French and my native language is Danish.

However, from a brand communication perspective, I have always considered that you need to cater to this “81% National pride” population, or rather, that the ideal way of communicating with your audience is in their national language. Firstly, your domain name should be a local domain extension (.es .fr .pl etc). In the long run this will give the best result including for SEO. Secondly, your website should be in the language of the audience it speaks to.

Consider Search Marketing campaigns. In your keyword research you will come across English language keywords – should you then do English language ads to go with them? Well no, not at all. You should keep your English keyword as a target, avoid keyword insertion (in paid search) and then do you ads in the language of the website. The ad is like an extension of your website so a change of language between the ad and the site would not make sense to the end user and you would loose him/her.

Finally, you touch upon the economics of multilingual content marketing. There is no doubt that you ideally need to be as local as possible. However, users are not stupid and I think local language homepages with links to more complete versions of a website in another language can be an acceptable compromise and first step for those who really can’t afford to localize it all.

Think of it as a simple question of #format and #communication channel. In the “French market” channel you need the “French language” format of your content. Same as you need a “200 x 200 banner” in certain ad spots and a “html mail” format for your emailing campaigns.

Avoid being one of those who send the wrong #format through the wrong #channel – we all know them! They published their TV spots on Youtube without modification, their websites could only be seen on a local server because they were too long to load, they sent their PDF brochures by mail with a title saying “please read attached” and they have yet to publish a tweet because the copy provided by the copywriter hasn’t been validated internally…

Anders

Great Article.

I think in Spain for example we have alot to improve… even if the majority of Spaniards are bilinguals (speak Spanish and the local dialect, as Catalan, Vasc, Galician,etc) within our nature… schools, government and private companies should incentivise students and employers with languages programs, specially for English.

Very interesting data.

Thank

The majority of Spaniards are not bilingual or even know a foreign language. This is, I believe, typical of countries whose mother tongue has 100s of millions of native speakers. Another fallacy is that in Spain we are erroneously encouraged to believe that e.g. learning English will give you a well-paid job. Learning another language requires time and financial investment, and most Hispanophones do not need a second language whereas Scandinavians and The Dutch may as their languages are not global.

@Anders:

Firstly, great comments, great advice. Thanks.

Secondly, it’s hard for me to disagree with anything you mention. What’s fairly ironic, though, in regards to the “National Pride” is that, as I touch briefly upon in the article, the internet is largely considered as this unifying force which drives forward globalisation at an unprecedented level; however, I think the irony lies in the fact that, as the world is getting increasingly homogenised due to globalisation, we’re witnessing counter movements in large numbers at the national level who fight for preserving their own culture, language and general sense of belonging. This further underlines the importance of being as local as possible, as you point out.

You also make a very important point in that ads are an extension of your website. Far too often when searching, I encounter examples where native ad copy is about the only aspect that appear to go into companies’ localisation strategies. If you deploy such a strategy in European countries where multilingual proficiency is relatively low, such as Italy and Portugal, these local language ads might drive people to your website (or other desired destination), but you can be absolutely certain that most won’t stay for long when they realise that the site is in another language, potentially displays prices in a different currency, and ultimately leaves the potential customer with little to no inclination to purchase due to a severe lack of locally rooted trust anchors.

I dig your wrong #format wrong #channel by the way. I believe it’s all about integrating all your communication/customer touchpoints, however knowing that each channel have to be treated differently. This certainly is an easy thing to postulate, yet it remains extremely difficult to master in practice.

@Immanuel, Thank you for this article, very interesting.

@Ricardo,

I just read your comment, I totally agree with you. Most of the people in Spain has to improve their English and help the country become more global (Needless to say, there are some people who has still problems with spanish even the non bilinguals.

I wanted to add that Vasc, Galician and Catalan should not be referred as “local dialects”, since they are completely independent languages. (A only spanish speaking person would not understand a word of those languages when spoken quick or with strong accents) 🙂 No hard feelings! 🙂

The right second or third language for Europe…and probably the rest of the world is Esperanto. If you are principled you will know the difference between struggling against native speakers of English and being an EQUAL in Esperanto, whether you are Russian, French, German or Chinese or like myself a native speaker of English (who detests privilege) from the USA.

The article was very interesting. It shows that the predominance of languages, or their popularity, is in constant fluctuation – some becoming more popular than others – others losing favor. It is also interesting to see that such fluctuations can also be observed over fairly short periods of time, as shown in the differences with the 2005 survey. Lastly, the decline of languages such as Russian and German in countries such as Poland and Slovakia, shows that economic and political changes in a region can greatly affect the “motivation” to learn certain foreign languages. All of this poses some interesting questions regarding the future of English, despite its overwhelming dominance as a second language choice in Europe. Could economic and political changes, e.g. the decline of the US economy in favor of BRIC countries, lead to a lesser interest in English? In such a case, would a new dominant language emerge? If so, which one? When one realizes the time, effort, and investment that learning a foreign language requires, such fluctuations and uncertain future, should make us think about investing in true international languages such as Esperanto, as the common second language of Europe and of the world. This would protect national and regional languages while offering a stable tool of international communication that would no longer be subject to political and economic changes. The ease of learning Esperanto would also bring multilingualism within everyone’s reach. No more for long studies, exchange programs abroad, or expensive teaching programs – everyone from the peasant isolated in a village to the IV League graduate living in NYC, would be able to communicate on a global scale.

I think there is a common misconception that everybody is Europe speaks English, but like your data shows above that is clearly not the case. Even a persons second language isn’t always English, as for certain people it makes more sense to learn French, German or Spanish if they live in a bordering country. So it’s no surprise that multilingualism isn’t actually on the rise. I think people need to know this before they translate their website into a language that they think is relevant to their customers but actually isn’t.

While the article is globally correct, I was really shocked to see *very* serious mistakes in the diagram where you compare the foreign languages. To stated that just 16% of the people speak Spanish in SPAIN is absolutely ridiculous, as it is the official language of that country. Even worse, according to this diagram only 10% of the people in the UK speak English and only 10% of the people in Germany speak German!

Sorry, but such stupid statements discredit totally what would be otherwise a very interesting article.

I appreciate your comment, but I think you’ve misunderstood the graph. The languages listed are foreign languages only. Take Denmark, for example, where Danish isn’t listed at all. Does that mean that 0% of the Danish population speak Danish? Or that no one in the Netherlands speak Dutch, and so on and so forth?

Spain, the UK and Germany — the three countries which you mention — all have large immigrant populations, who don’t have English, Spanish or German, respectively, as their mother tongue – hence, it’s considered a foreign language even if they live in that country.

Thanks for the informative article

I see that few countries speak Russian too so I’m happy about that!

Many people who travel to Russia or businesses that deal with Russia have to invariably engage a translator as most Russians will not speak any other language other than Russian.

It is sad to see that most of Europe in spite of having ties both cultural and economic decide to go with USA in the recent crisis on Ukraine.

Awesome post.